The Best Secret of the Masters

Currently there is a revival of interest in the techniques of historic master painters. Artists sometimes are fascinated by the search for a “secret” that makes old master paintings last so long and look so great. One often mentioned “secret” is the development of a stable varnish by the Flemish painters Hubert and Jan Van Eyck. Likewise, it is sometimes said that Leonardo developed a “secret” technique where he added beeswax to his medium, reducing the problem of yellowing in the paint. This technique was supposedly kept secret in Italian ateliers for nearly three centuries, and helped give Italian artists wide recognition throughout Europe. In the eighteenth century, the painter Sir Joshua Reynolds, suggested that the “secret” was actually a red iron oxide pigment called Sinopia named after the Turkish city Sinop. Reynolds believed the secret of this pigment had been lost in history, and only rediscovered in the 1600s.

Ancient artists used materials from the environment, such as clay, charcoal, and blood. The Lascaux painters used various forms of iron oxide derived from clay. These clays were mixed with water to make red, brown and yellow hues. Somewhere along the historical line, oils were discovered for use in painting. The Egyptians knew how to extract oil from plant substances, and it is not hard to imagine someone observing oil drying on utensils after cooking a meal. However, the first solid evidence of art resembling what we know as oil painting actually comes from Afghanistan. Dating from as early as 650 C.E., artists in Afghanistan used various oils in combination with pigments to create images of Buddhas sitting in meditation. Research is ongoing regarding the exact materials used with with these paintings, but so far it is posited that natural resin, plant gum, drying oil and animal protein were part of the ingredients. Other substances such as iron oxide clay, charcoal, and mineral colors were readily available on the Silk Road, and were likely used in the paintings.

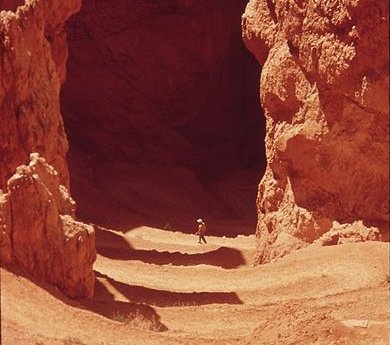

Rock formations in Bryce Canyon, Utah composed largely of iron oxide, courtesy of Boyd Norton

So, what is so special about iron oxide? It turns out that iron oxides have some very interesting and unique qualities. First of all, they work quite well with oils in painting because they facilitate drying. They help the oils dry faster and more thoroughly. In contrast, the widely used pigment titanium white has no drying action at all. Iron oxides are also durable. They are used in paints for anti-corrosion coatings, such as you see on large red metal construction beams. Because some oils such as poppy seed and safflower have less tendency to yellow, artists and paint manufacturers may use them for whites and blues. Since safflower and poppy seed oil dry slower, sometimes metal driers have been added to them to speed up the oxidation process. However, cobalt and lead driers are to be used with caution in art materials because of concerns about toxicity. The iron oxides, in contrast, are still considered safe.

Drawing from the Sinopia Museum in Pisa, Italy

By Joanbanjo (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

There is a Sinopia Museum in Pisa, Italy, that specializes in old iron oxide drawings made in the fourteenth century. The images were created by multiple artists as guides for frescoes. In an effort to save the frescoes during World War II they were pulled off the wall, and the sinopia drawings were discovered underneath. Like the Lascaux drawings, these have held up over centuries. Iron oxide pigments are a perfect match for painting. Many of the old masters such as Rubens, Rembrandt, and Franz Halls never used more than five to seven colors, mostly iron oxides. It is great that we have hundreds of new pigments and other resources to use. But it is equally important that we not forget the history of painting, and the discovery that some materials, such as iron oxides, work extremely well!

The Sinopia Museum in Pisa, Italy

By Geobia (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons