Color-field Painting, Freedom, and Willy Richardson’s Immersive Art

A Painter Who Became Allergic to Paint

An essay by Friedhard Kiekeben and Willy Richardson

Reproduced with reprint permission by nontoxicprint.com

The Santa Fe based artist Willy Bo Richardson completed his MFA in painting

from Pratt Institute NY in 2000. Since then, his lusciously intense, and

immersive color field paintings on aluminum, canvas and paper have received

considerable critical and commercial success. The work resonates with the bold history of geometric abstraction and a more conceptual approach to painting. Despite the dazzle of intense, luminous

pigmentation, carefully built layers and translucent oil glazes, the work offers

unique visual experiences to viewers that defy easy explanation and

categorization.

Richardson’s work is decidedly abstract, and to speak with Clement Greenberg: ‘modernist painting …has not

abandoned the representation of recognizable objects in principle. What it has abandoned in principle is the

representation of the kind of space that recognizable objects can inhabit. (lecture ‘Modernist Painting’, 1960).’

Willy Bo Richardson’s technique borrows from the Dutch tradition of layered oil painting –– building images from

lean to fat –– , but his preferred current painting substrates are large-scale aluminum panels, a thoroughly

industrial material, rather than the stretched canvases of old. Also his color palette is more at home with a jazzy

mix of 1980s neons and day-glo colors than the more muted and carefully orchestrated hues of the old masters.

Despite a very carefully developed and complex painting technique – and its avoidance of the flat color field

approach of many contemporary painters – the work is firmly modernist and of our time.

Painting and the New Mexico Light

By providing intense visual experiences to the viewer, this work places itself among other notable artists who

likewise found tremendous inspiration in the spaces, light and atmosphere of New Mexico, and found new ways

to place the experience of color at the center of their practice: Agnes Martin, Georgia O’Keefe, and James

Turrell, to name but a few. And In ‘Specific Objects’ Donald Judd, another lover of the Southern light, wrote:

‘Half or more of the best new work in the last few years has been neither painting nor sculpture. Usually it has

been related, closely or distantly, to one or the other’. Perhaps, one of the most important artists Richardson

takes inspiration from is Mark Rothko, both in terms of a luminous color field approach, and in

his painting technique.

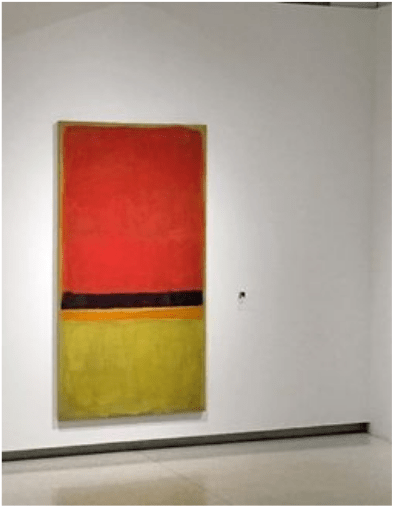

Mark Rothko, ‘untitled’, 1953,

Walker Art Gallery, Minneapolis,

picture by J. Riedl

The Walker Art Gallery writes: “From 1938 onwards…

Rothko turned away from current events

and committed himself to ‘the forms of the archaic

and the myths from which they have stemmed’.

and ‘After 1950…

he also ceased publishing statements about his

aims and ideas, confiding to Newman that he had

‘nothing to say in words’

about what he was doing on canvas.”

‘Music to Drive To 9’,

53 x 114inches (diptych),

oil on canvas,

at Richard Levy Gallery exhibition

“That’s Where You Need to Be”

‘Clockwork for Oracles 1’,

29 x 93 (triptych),

oil on canvas

In 2016, Levy Gallery wrote: ‘Richardson stretches vertical bands of color so intense across each canvas that they

seem to crackle like neon. He has described his act of painting as a sort of meditation, a give-and-take with gravity

and the universal laws that determine our experience of the physical world…

The stripes are singular yet interrelated. Gestural under-layers with both dark and light elements offset his more

disciplined vertical strokes — those so saturated that they vibrate, gripping the viewer, and each canvas’s humming

field suspends the sensation of time.’

Others point to the musical nature of the work: ‘Using watercolors and oil, Richardson paints vertical lines with

uneven brushstrokes, rendered precisely so that each stroke reads as intentional. In his works on both canvas and

paper the oil paint seems to flow quite smoothly—showing no signs of being clogged by the teethy texture canvas

often offers. Richardson’s naming schema seems especially Kandinsky-esque in form, as he frequently references

music, and the synesthetic associations between sight and sound. In this way, Richardson’s dedication to verticality

and use of vibrant colors seem especially significant in a sonic sense.’ (Artsy).

‘Wet Snow Falls from a Pine Branch (triptych)’,

57x159inches,

oil on canvas,

applying final picture varnish in studio

Rhythmic Compositions

Richardson shared his own thoughts on the sequential and rhythmic nature of his vertical and panoramic

compositions and vibrant bands of color. ‘I find myself at the jumping point. I know this to be as a dream, and from

here I lift off. Please excuse my abstraction in this coming paragraph. It’s for this reason painting is my medium. I

see vertical strokes as the launch pad. It is the last bastion of creativity. It is not total freedom. It is the tension of

knowing freedom is there and fighting against the limited structure that tethers us to this cycle. When I paint, I am

aware of my condition, that my paintings will never be perfect, nor will anything else in this world we share, but I

will strive towards perfection, towards freedom.’

Many artists seeking — and often finding — freedom of expression also encounter constraints of a different kind:

many of the known art making materials and processes entail numerous chemical and physical hazards

threatening the artist’s health, through frequent and prolonged exposure to toxins. In the following, the artist

shares his recent experiences with these issues.

a respirator with organic vapor cartridge

in the artist’s studio

Learning About Safety and Art

I learned general health and safety practices working as a painting tech at Cooper Union in New York for 7

years, and then teaching as an adjunct professor in Santa Fe for 7 years. I always wished to have safe studio

habits, but was often lazy in my own studio, and university ventilation systems and practices were not adequate.

Many of the solvents and mediums artists use would be taken much more seriously in a science lab.

Unfortunately, I come from the generation that was taught to paint with damar, stand oil and turpentine. I

explored many mediums over the years, including products from the hardware store. Eventually I settled on an

alkyd medium and odorless mineral sprits (OMS). I explored less toxic alternatives, but wasn’t happy with the

results and stuck with what I knew. Old habits and inertia landed me in the middle of a health crisis.

It was after I became sensitized to solvents that safety in the studio became priority number one. Now I can only

paint with the highest standard for low toxicity and safe studio practices. Otherwise I will quickly become light

headed and go home with a headache and nausea. So I’m not working with theories. If I mess up, I’m sick. I am

currently able to work with oil paints and mediums in a traditional way while inhaling a minimal amount of fumes

toxic OMS. I would like to share some of what I’ve learned about safe studio practices. I don’t consider myself

an expert. Some of what I know may be outdated or incorrect. I am learning as time goes on and wish to have a

completely non-toxic studio in the future.

February, last year, I taught a painting class on color theory, and oil glaze techniques at Santa Fe University.

Early in the semester I went home with a headache and nausea. I hadn’t exposed myself to anything unusual

that day. The next morning, I woke up with what felt like a hangover, and from that day on I could no longer set

foot in my painting classroom without feeling sick the rest of the day. I also could no longer enter my own studio!

I had become sensitized to the solvents and cleaning agents used in my painting practice.

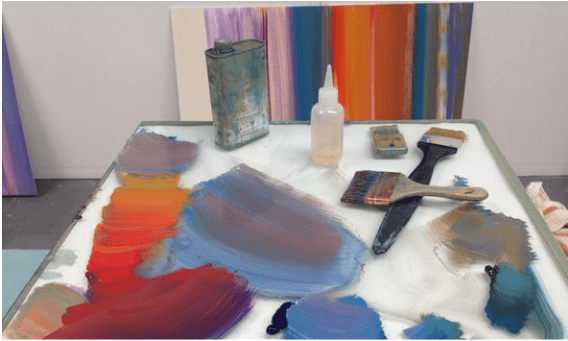

Painting Palette

A life of Painting turned upside down

My life turned upside-down, as I learned to cope with the sudden onset of these new physical ailments related to my

work. Aside from the emotions of fearing I may never paint again, I became physically sick when I walked down the

detergent isle at a grocery store, entered a mechanic shop, or inadvertently set foot in a room where someone was

painting their nails. On the worst day, I simply walked past the janitor cleaning cart at my daughter’s school and

subsequently felt sick for hours afterwards. As well as nausea and headache, I had the new experience of my reptilian

brain’s fight or flight response, along with “brain fog,” which felt like early onset dementia.

You can imagine this past year was quite a ride. I revamped the painting studios at the school — switched students to a

solvent-free painting medium and canola oil for washing brushes. However, I did not want to short change my class, so I

continued to teach a traditional technique that required small amounts of mineral spirits to build “lean to fat” glaze layers

of oil. To avoid consistent nausea and headaches, I finished up (what would ultimately be my last semester teaching at

SFUAD) with the students painting en plein air.

I changed my own studio practices too: solvent-free mediums, new ventilation system, and a respirator when working

long hours or working on large surfaces with mineral spirits. Thankfully I had guidance from chemist, artist, and one of

our nation’s leading experts in industrial hygiene, Monona Rossol. I met Monona when she was consulting SFUAD, and

then by chance sat next to her on the red-eye to New York. She is a national treasure and worth looking up.

(Arts, Crafts & Theater Safety)

‘Seven Sisters’,

53 x57 in,

oil on canvas

In the studio

Dealing with chemical sensitivity

One of the known, and more obvious, cures to chemical sensitivity is to stay away from chemicals. For nearly six months, I

spent as much time as possible in fresh air, both hiking and skiing. Sounds like fun right? I relied on a surplus of paintings

in my studio to sustain my income. (Fortunately, 2016 was my best year ever in sales!). I sought out the healing council of

friends, and had an unexpected encounter with a Lakota heyoka when I was in Standing Rock, ND last Fall. I am further

convinced this is a shared dream, and any situation can be transformed.

Within the past two months, I have only had one episode, which is a major improvement. I was in my studio, starting to get

brain fog and went home feeling sick. It didn’t make sense because I was working with watercolors that week. I called my

studio neighbors to inquire and was surprised to hear, “nothing toxic going on over here, just cleaning floors with plain ol’

bleach and Fabuloso.” Bingo! I will assume all my readers understand the level of toxicity in those two products, especially

combined. I bought my neighbors non-toxic cleaners. Problem solved.

Today, I am happy to say that my condition has improved and is now manageable. I have new rules about diet, studio

practice and lifestyle, but I am — for the most part — back in action! I no longer wonder, Will I feel sick today? Also during

the time away from my studio, I was able to reflect on my work and put new energy into my vision and career. I became

inspired to work on new, long-term projects, which are currently in motion but I cannot announce yet. Be ready for exciting

news!