Pigments and Binders

On Pigments

by Debu Barve

— Remember c o l o r s ?

This question sounds silly

because we really don’t perform any

conscious process of recollecting

specifics about colors (most of the time!).

Every object we see, the information

we gather visually,

our memories, imaginations and even

our dreams have colors.

(Reproduced with reprint permission by nontoxicprint.com)

This introduction to the topic could very easily begin to move in

several different directions at this point. For instance if we

mention ‘dreams’ then we could bring in Sigmund Freud! But

here when we say ‘colors’, (which is what we are going to say –

we are going to talk about ‘Pigments’).

Now when we begin talking about pigments, we still have

multiple things that we can discuss: physical basis, chemical

understanding, technical understanding, historical (history of

pigments, not history of art), artistic, etc.

Even from an artistic point of view, there are multiple aspects

which will very soon convert this small intro into a good fat

datasheet. (No, this is not going to happen!)

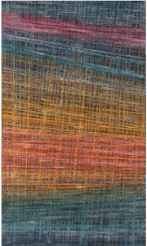

Bibiana Saucedo

Acrylic on canvas 2023

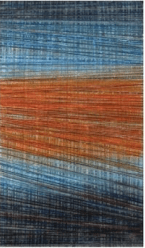

Joan Snyder

Summer, 1970

Oil and graphite on canvas, 56x91cm

What is a pigment?

A pigment is a dry coloring matter, usually an insoluble powder.

When these dry colorants are mixed with binders also called

‘vehicles’ (such as linseed oil, resins, acrylic, wax etc.) we get

various types of paints. But besides pigments and binders, paints

can also contain various adhesives, stabilizers, preservatives

and antioxidants (dryers) etc.

This means watercolors, pastels, gouache, color pencils, acrylic

paints or oil paints, they usually share same pigments but

different binders.

Mauve: How One Man Invented a Color That

Changed the World,

Paperback – May 17, 2002

by Simon Garfield (Author)

Pigment Categories

Pigments have three basic categories:

1. Organic substances (made from natural sources. Color

example: Rose Madder)

2. Inorganic (made from sources like minerals and metals. Color

example: Burnt Sienna)

3. Synthetic pigments (artificially manufactured. Color Example:

Cobalt Blue)

Pigments Types

Artistically, there are 3 broadly defined pigment types:

- Earth colors – ochres, siennas, umbers, Mars colors

- Traditional colors – cobalts, cadmiums, titanium, ultramarines

- Modern colors – phthalocyanines, quinacridones, perylenes, pyrrols

Pigments made from natural sources have been used for

centuries, but most pigments used today are either inorganic, or

synthetic organic ones, (containing a carbon atom structure

similar to the original organic pigment).

The industrial and chemical revolution in the 19th century

changed the scenario rapidly and today what we get as

consumer colors are mostly made out of synthetic pigments.

Historically and culturally, many famous natural pigments have

been replaced with synthetic pigments, while retaining their

historic names. It is indeed good to know about colors more than

just their names!

Debu Barve

The Existence, Acrylic, 20 in. x 12 in.

Debu Barve

The Sound, Acrylic, 20 in. x 12 in.

DEBU BARVE ART BLOG

I’m an artist living in Pune, India. Besides painting, I love reading about art, history and culture.

And how about some trivia on pigments?

More than 15,000 years ago cavemen began to use color to

decorate cave walls. These were earth pigments, yellow earth

(Ochre), red earth and white chalk. In addition they used

carbon (Lamp) black by collecting the soot from burning

animal fats.

Ancient Romans used to import indigo as a pigment from

India by Arab merchants. They used it for medicinal and

cosmetic purposes. It was an expensive luxury item!

Indian Yellow was once produced by collecting the

urine of cattle that had been fed only mango leaves. Modern

hues of Indian Yellow are made from synthetic pigments.

Vermilion was developed in China around 2,000 years

before Romans started using it. Vermilion was made by

heating mercury and sulphur.

Ultramarine was originally produced from the semi-

precious stone lapis lazuli. In the 1820’s a national prize of

6,000 francs was offered in France to anyone who could

discover a method of artificially making ultramarine at a cost

of less than 300 francs per kilo. J B Guimet succeeded in

1828. Known as French Ultramarine ever since, the pigment

is chemically identical to genuine ultramarine.

Lac is a red colorant originally made in India, which gave

rise to the term ‘Lake’, meaning any transparent dye-based

color precipitated on an inert pigment base, used for glazing.

During the High Renaissance in Italy, Lac was the third most

expensive pigment (after gold and Ultramarine), but most

artists thought it worth the expense.

In 14th century, the Italians developed the range of earth

pigments by roasting clays from places called Sienna and

Umbria to make the deep rich red of Burnt Sienna and the

rich brown of Burnt Umber.

The oil paint pigment van Dyck brown is named after

17th century’s great Flemish painter

Anthony van Dyck.

Emerald Green was a very popular wallpaper color but

unfortunately in damp conditions arsenical fumes were

released from it. It is thought that Napoleon died as a result of

arsenic poisoning from the wallpaper in his prison home on

the island St. Helena.

Payne’s gray is named after the 18th century watercolorist

William Payne, this dark blue-grey colorant combines

ultramarine and black, or Ultramarine and Sienna. It was used

by artists as a pigment, and also as a mixer instead of black.

Ultramarine Pigment and Ultramarine Purple

pigment Safety – some special advice for artists

and hobby paint makers

Ultramarine Pigment and Ultramarine Purple / Violet / Rose Pigment Powders

These pigments are commonly presumed to be

nontoxic and stable (and advertised as such),

yet the molecular structure is very unstable and reactive,

under a variety of circumstances.

——- hydrogen sulfide danger ! ——-

This rare and very unusual gas,

when inhaled during paint mixing,

can cause paralysis,

and may be lethal

even at moderate concentration (from 100ppm).

…even a single inhalation of this gas may be

life threatening to the artist.

The various ultramarine pigments have become very popular with artists wishing to make their own paints. Both ultramarine and ultramarine purple / rose pigments can safely be mixed with linseed or walnut oil by artists in their own studio. This is not thought to be of concern, as the oil safely encapsulates the pigment grains.

But both ultramarine and ultramarine purple pigments should not be mixed with aqueous binders and mediums without special precautions. Confusingly, the dry pigment powders are considered relatively safe, and are classed as ‘nontoxic’ in sds documentation. Even these dry powders by themselves may emit sulfuric vapors, depending on conditions and the chemical composition of the product used.

In practice (as we know from first hand experience), mixing any kind of water based paint —- with gouache, acrylic, or watercolor binders —- in an artists studio from ultramarine pigments (synthetic or as mineral Lapislazuli) is strongly advised against, as it can cause the production of very dangerous gases. The complex molecule of lapis-based powders is known to contain large amounts of unstable sulfur atoms within their matrix, which when liberated, for instance through the addition of trace amounts of lead, hydrochloric, or any other acid or alkaline, can easily produce poisonous gases with a rotten egg smell which are poisonous and in higher concentrations can even be lethal through nhalation, while mixing paint.

(note: a sulfuric smell is not always present or noticeable).

In order to make this mixing process manageable and safer for artists, a ventilated / extracted fume hood would need to be used while paint mixing, and a face mask with inorganic active carbon cartridges also needs to be worn, as a minimum precaution. However, once mixed, the paint should be stable and without further emissions.

Overall, it is recommended to use ready mixed, shop bought, ultramarine paint products in preference to mixing it yourself.

The pigment industry is aware of these emission issues and internally refers to the problem as ‘the unreacted sulfur problem’ within the synthetic ultramarine ‘chromosphere’ (molecule) that is being synthesized during a complex, sulfur rich, manufacturing process that mimics the natural formation of lapislazuli rocks and minerals.

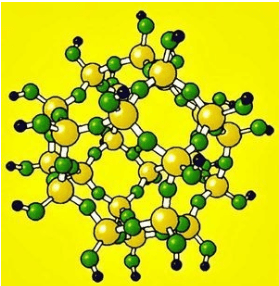

Illustration of a typical lapis lazuli or synthetic ultramarine

molecule (chromophore); natural and synthetic variants are considered

almost identical. Lapis (Lazurite / Azurite) is considered one of the most complex minerals

found in nature.

GUIDE:

black —- Si4+ / Al3+ |

yellow — Na+ | green — S3-

The abundance and surplus of sulfides is clearly visible,

and this accounts for the latent potential for toxicity.

WHAT ABOUT FACTORY MADE ULTRAMARINE PAINTS… ARE THESE SAFE?

Ultramarine Paint and Ammonia

Considering the real and present danger posed by ultramarine pigment powders, the question arises if ready mixed waterbased paints, such as ultramarine acrylics are safe or not. The many acrylic paint manufacturers not only assure us of the safety of the ultramarine paint tubes, but also invariable place a ‘nontoxic’ symbol on the tube.

Looking at the basic chemistry involved when adding water to ultramarine acrylic, however gives cause for possible concern. Almost all acrylic paints contain significant amounts of ammonia, and this can often be detected by smell. Some products even contain a large amount of ammonia, as any acrylic painter will testify. The ultramarine chromophore molecule is largely constructed from aluminum and sodium atoms that create ‘cages’ within which large amounts of sulfide atoms are loosely trapped.

But both aluminum and sodium atoms are known to quickly dissolve in ammonia solution, possible in a heat-generating exothermic reaction.

Given these basic facts, it seems highly likely that at least some kinds of acrylic paint (e.g. those with high ammonia concentrations) are likely to produce poisonous hydrogen sulfide emissions during paint mixing and application by the artist.

Bio-resins and acrylics:

Fast-paced Research into sustainable plastics

Research into bio-based acrylics and resins has recently gone past the R+D stage, and we can expect innovative polymer paint products for artists and decorating to become available within the next few years.

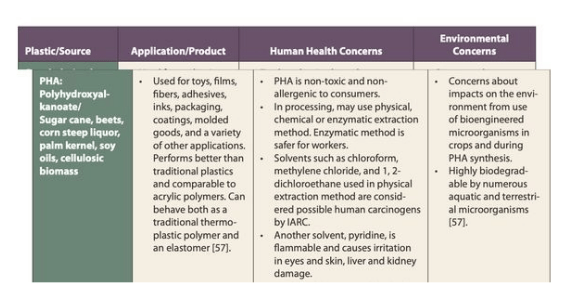

PHA — Polyhydroxyalkanoate — seems to be among the most promising base ingredients for truly eco-based polymer paints. Below is a listing of some of the key characteristics by the Lowell Center for Sustainable Production • University of Massachusetts Lowell